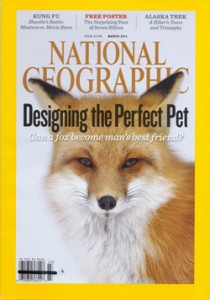

The biology of tameness is at the heart of a thought-provoking article in the March 2011 issue of National Geographic.

The biology of tameness is at the heart of a thought-provoking article in the March 2011 issue of National Geographic.

Is there a genetic factor that can account for the reason a relatively few animal species have proved capable of being domesticated? What, for instance, accounts for the difference in tractability between the horse and the zebra, or the dog and the fox?

In 1959, researchers in Siberia began selectively breeding silver foxes for a single trait – friendliness toward humans. By the fourth generation, the foxes began exhibiting tame behavior; by the ninth generation, they also displayed phenotypical signs of domestication, such as spotted fur and coat color variation, as well as curly tails, and floppy ears in pups.

While scientists agree that domestication is not a quality trained into an individual, but one bred into an entire population through generations of close proximity to humans, the question of inherent adaptability remains.

“At the beginning of the domestication process, only natural selection was at work,” researcher Lyudmila Trut points out in the article. “Down the road, this natural selection was replaced with artificial selection.”

Meanwhile, the Institute of Cytology and Genetics in Novosibirsk, Siberia, which has been forced to manage its population by selling to fur farms, is seeking to obtain permits to sell their surplus of tame foxes as pets, both at home and in other countries.