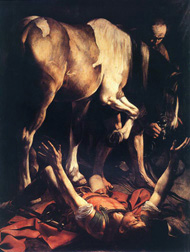

Paint horses in Renaissance art? They were referred to as piebalds and one stunning example appears in a work by Caravaggio, the subject of a recent article in the Wall Street Journal.

Paint horses in Renaissance art? They were referred to as piebalds and one stunning example appears in a work by Caravaggio, the subject of a recent article in the Wall Street Journal.

The Conversion of Saint Paul (1601) by Michelangelo Merisi, the seventeenth century Italian artist known as Caravaggio, is dominated by a bay and white horse that reflects bewilderment, as Paul, who has fallen from its back in a trance, writhes on the ground.

On first seeing the work, I was reminded of a story that Buster Welch told me about an impressive sculpture of a mounted cowboy. Buster stood in front of the piece for several minutes admiring the artist’s handiwork, until he noticed that the cowboy’s lariat was hanging from the wrong side of the saddle.

“That just ruined the whole thing for me,” Buster told me.

Contrary to Buster’s experience, the piebald horse didn’t “ruin” the picture for me. Because of my interest in horses and a meager knowledge of art, it enthralled me. This is a horse you could throw a saddle on today, not the stylistic steeds of Durer or da Vinci.

Criticized by his contemporaries for the sensational realism that he employed in his art, Caravaggio was the bad boy of the Baroque period. He was also a master of chiaroscuro, a technique that employs a dramatic use of light against a dark canvas. The white withers, shoulder, and forearm of Paul’s mount in the Conversion of Saint Paul (1601) draws the eye to his master in the lower right-hand corner, bathed in the light of revelation. The horse’s kind and concerned eye is mirrored in the face above his head of Paul’s companion, standing behind the horse and holding his bit.

Where did the concept of a Paint horse in Paul’s conversion originate? A horse was never mentioned by Paul in his own accounts (from his Letters) of his conversion. Nor was a horse mentioned in the accounts given in the Book of Acts of the New Testament. However, a fallen horseman symbolized the fall of pride in man in medieval society.

Caravaggio made Paul’s horse solid grey in his first version of the painting (Michelangelo also portrayed the horse as gray in his 1545 fresco), which because of a dramatically different composition has none of the impact of the second version. But earlier Italian Renaissance artists Carracci and Brescia painted the same scene with piebalds. Brescia’s horse (pictured) even has a white forearm and, characteristic of the period, Brescia’s and Carracci’s horses are stylistically plump, the equine equivalents of cherubs.

Caravaggio made Paul’s horse solid grey in his first version of the painting (Michelangelo also portrayed the horse as gray in his 1545 fresco), which because of a dramatically different composition has none of the impact of the second version. But earlier Italian Renaissance artists Carracci and Brescia painted the same scene with piebalds. Brescia’s horse (pictured) even has a white forearm and, characteristic of the period, Brescia’s and Carracci’s horses are stylistically plump, the equine equivalents of cherubs.

Piebald coloring was connected to Greek mythology through Balius, one of Achilles’ chariot horses; in the Middle Ages the color was associated with magic and the netherworld. Baroque artists Reni and Guercino portrayed Paint chariot horses in their ceiling frescoes with Apollo and Aurora.

To see the Conversion of Saint Paul you must go to the Cerasi Chapel of the Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome, but if you are in Fort Worth, the Kimbell Art Museum, directly across the street from Will Rogers Coliseum, has a magnificent work by Caravaggio titled The Cardsharps.

Coincidentally, today’s Wall Street Journal online featured a video about an amateur Italian sleuth who is determined to track down the bones of Caravaggio and determine the cause of his death (The artist disappeared in 1610, after he was convicted of murder in the death of his lover’s husband).