It was also adapted for my book, Cutting Horse Classics

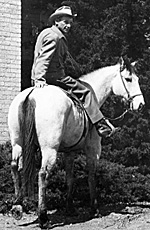

“I haven’t had a pair of boots on in over a year,” admits Emry Birdwell, shaking his head in disgust.

Last year, Birdwell was tossed over a four-foot fence by a 2,000-pound bull. “I’ve been down and under ‘em and everywhere else, but that was the worst wreck I’ve ever had,” admits the 86-year-old rancher.

Last year, Birdwell was tossed over a four-foot fence by a 2,000-pound bull. “I’ve been down and under ‘em and everywhere else, but that was the worst wreck I’ve ever had,” admits the 86-year-old rancher.

One of the thirteen founders of the National Cutting Horse Association, Birdwell has seldom been afoot. As a boy he helped with chores on the family farm in Palo Pinto County, Texas, not far from his present home. His father’s family came to Texas from Tennessee in 1847, and lost all their cattle in “the great freeze” of 1886.

Birdwell left school at fourteen. Breaking colts for five dollars a head made more sense to a ranch boy than reciting poetry. Not long after he quit school, Birdwell hired on with some of the big cattle outfits. He worked roundups on the Swenson Ranch in West Texas and spent a year with the Muleshoe outfit near Deming, New Mexico.

Birdwell left school at fourteen. Breaking colts for five dollars a head made more sense to a ranch boy than reciting poetry. Not long after he quit school, Birdwell hired on with some of the big cattle outfits. He worked roundups on the Swenson Ranch in West Texas and spent a year with the Muleshoe outfit near Deming, New Mexico.

“They give me eleven head of horses and nine of them was broncs,” Birdwell reminisces about his first mount at the Swenson Ranch.

Until five years ago, Birdwell still started and trained his own horses. “I’m paying $450 a month to get five head of horses broke now,” he says. “That’s a lot of difference from what I used to get.

“I never did break a horse back then until they were three years old. They would make better horses quicker. Of course, three years old, some of them were pretty rank.”

Birdwell’s horse-breaking experience put him in good stead for bronc riding. In 1934, he won the Stamford Rodeo saddle bronc contest and a trophy saddle.

“I was only bucked off once,” Birdwell recalls of his rodeo days. “If you don’t ride one pretty good, you won’t make any money.”

Some of the early rodeos also included cutting horse competition, an event that fitted Birdwell as comfortably as his boots. “That’s all I ever did was work cattle,” says Birdwell. “Whenever I was gathering cattle, I’d cut some of them and use my horse.

“I trained my horses right there in my pens and I knew how much they could stand. I was riding more than one horse all the time.”

One of the horses that Birdwell rode was a dun gelding he called Boots. Boots had been raised on a ranch near Palo Pinto and was just two when Birdwell paid $150 for him.

“That was back when horses were cheap,” says Birdwell. “I don’t know how he was bred. But he was one of the best horses I ever put a saddle on.”

Boots worked for a living and was so good at his job that Birdwell entered him in the 1946 Fort Worth Fat Stock Show Rodeo. The day before the prestigious event, Birdwell and his gelding were still ranching.

“I was pasturing 150 heifers,” remembers Birdwell. “That day I cut every one of them through a gate. I’d just pull up every once in a while and lets Boots rest.

“Nowadays, if you worked 150 cattle on a horse, it would just kill them. But I rode the horse every day. I used him and he was tough.”

Boots was tough in the show arena, too. He beat the top horses of the day, the black gelding, ridden by George Glasscock for Benny Binion, owner of Las Vegas’ Horseshoe Casino.

Binion’s gelding became the first NCHA World Champion in 1946 and held the title for the next two years. But Boots whipped him at Fort Worth in 1946 and 1947, as well.

Birdwell figured Boots could have been world champion, but ranching came first. “George Glasscock could go wherever he wanted to go,” explains Birdwell. “He had the where-with-all to go. But I didn’t. I had to stay on the ranch and work.”

Birdwell figured Boots could have been world champion, but ranching came first. “George Glasscock could go wherever he wanted to go,” explains Birdwell. “He had the where-with-all to go. But I didn’t. I had to stay on the ranch and work.”