Swine, those dirty pigs, get the credit for the current flu pandemic. But, I wondered, have horses recently transmitted a potentially fatal virus to humans?

It turns out they have – the Hendra virus.

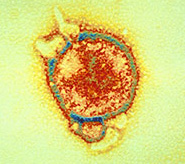

Hendra virus (photo credit CSIRO) is named for the Brisbane suburb in Queensland, where it was first identified in 1994, after causing the deaths of 14 horses in the stable of well-known Australian racehorse trainer, Vic Rail. Since then, 10 more outbreaks have occurred, most recently in August 2008, just 10 days after Queensland was officially cleared of equine influenza (EI).

Hendra virus (photo credit CSIRO) is named for the Brisbane suburb in Queensland, where it was first identified in 1994, after causing the deaths of 14 horses in the stable of well-known Australian racehorse trainer, Vic Rail. Since then, 10 more outbreaks have occurred, most recently in August 2008, just 10 days after Queensland was officially cleared of equine influenza (EI).

Scientists believe fruit bats are the natural “host” of the virus and that horses are infected through bat urine or saliva. All known Hendra outbreaks have occurred in Australia, where the fruit nectar-eating pteropid fruit bats are commonly known as “flying foxes.”

Although the first cases presented with flu-like symptoms, some later cases caused encephalitis. According to the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO), Australia’s national science agency and one of the largest and most diverse research agencies in the world, of the six known human cases of Hendra virus, all contracted directly from horses, three were fatal. So far there has been no evidence of human-to-human transmission.

Hendra virus is a close cousin to Nipah virus, which is transmitted to humans through close contact with pigs. The Nipah was responsible for more than 100 deaths in Malaysia in 1999 and devastated the country’s pork industry. In early 2004, 35 out of 47 humans infected with Nipah virus died in Bangladesh.

CSIRO is currently working on a vaccine for Hendra and Nipah viruses that has proved effective in cats, which are highly susceptible to the viruses. Scientists hope to have the vaccine ready to be licensed within three years, a critical timeframe, because there is evidence that the most recent Bangladesh outbreaks involved not only direct bat-to-human transmission but most likely, for the first time, human-to-human transmission.

In the meantime, researchers at Cornell University have recently discovered that choloroquine, an established drug used to prevent and treat malaria, is an effective inhibitor of infection by Hendra and Nipah and it is hoped that clinical trials can move forward rapidly.