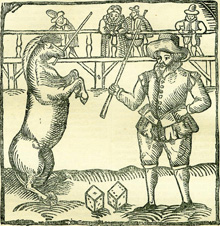

Morocco, “the dancing horse,” and his trainer, a Scotsman named Banks, were famous in London, Edinburg and Paris for their public performances during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. One exhibition took place on top of St. Paul’s Cathedral, the nave of which, at that time, was a center of trade for local merchants.

Morocco, “the dancing horse,” and his trainer, a Scotsman named Banks, were famous in London, Edinburg and Paris for their public performances during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. One exhibition took place on top of St. Paul’s Cathedral, the nave of which, at that time, was a center of trade for local merchants.

A servant, so the story goes, entreated his master to join the crowd gathered outside the cathedral to watch the spectacle. “Why do I need to look to the top to see a horse,” the man asked, “when I can see so many asses below?”

In addition to his ability to execute the Canary, a popular Elizabethan-era dance, Morocco, foaled around 1590 and probably of Arabian or Barb descent, could count with hoof taps the numbers on playing cards, and distinguish between red and black suits by the use of either his right or left hoof.

When instructed by Banks to find a particular spectator, Morocco would locate that person in the audience and pull him out with a gentle tug on his coat.

If Banks said that he was going to sell him as a cart horse, Morocco would lie down and play dead. But he would prance and trot, if told that he had been lent to carry a lady to court. He would always curtsy at the mention of the Queen of England, but bare his teeth and strike at the name of the King of Spain.

Although Banks had once referred to Morocco as a “spirit” in animal form and a rumor spread that the famous horse had been burned by order of the Pope, there is no evidence that this was the case. Although an English horse that had been taught to “know the cards” was burned alive at Lisbon in 1707, and Granger in his 1779 History of England, recalled a horse that had been taught several tricks being “put into the Inquisition.”